As a personal trainer and movement scientist, I often get asked for advice on fitness. (Go figure!) Whether it’s a friend, a family member, or a stranger on the internet with a cartoon character for a profile picture, I’m more than happy to share my two cents.

Of course, when I first started out in the industry I thought I needed to have all of the answers. I thought that if people came to realize I wasn’t all-knowing, they’d think less of me as a professional.

It turns out my thought process couldn’t have been further from the truth. In actuality, it takes a great deal of maturity and self-awareness to admit to your own limitations. People respect that.

Moreover, you can only parade around pretending to be smarter than everyone else for so long. Eventually, that shit catches up with you. Before it does, though, you’ll likely have no trouble dishing out plenty of unproductive — and potentially harmful — advice.

Which leads me to my motivation for this post. Lately, I’ve noticed a number of fitness professionals on the wrong end of the law in this regard. While this problem certainly isn’t a new one, it’s come to a head lately, to the point where I feel compelled to speak out against it.

I figured a constructive way to tackle this would be to provide a few examples of what’s NOT okay to do when you’re in a position of authority. I solemnly swear never to commit the offenses described below, and — for the sake of the people we educate — I beg of my peers to make the same promise hereafter.

Again, the unsuspecting general public will believe just about anything. They’re definitely not going to PubMed fact-check you.

Consider the following two statements:

I’ll be the first to admit that I don’t know everything. I still have a lot to learn, both as a trainer and a scientist. But I do know this: as fitness professionals, people rely on us to help them get fit and strong while staying injury-free. They also trust us not to lead them astray.

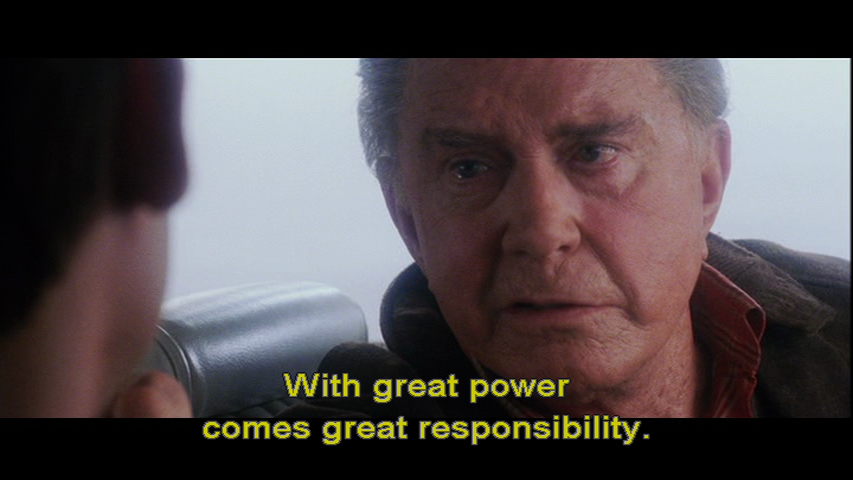

I believe it was Uncle Ben from Spiderman who said “with great power comes great responsibility.” Even if he was only a comic book character, his counsel couldn’t have been more spot on.

If you’re guilty of any of the above items, please stop. If you realize you’ve been supporting someone who’s guilty of the above items, please stop supporting them. Otherwise, you too are part of the problem.

Of course, when I first started out in the industry I thought I needed to have all of the answers. I thought that if people came to realize I wasn’t all-knowing, they’d think less of me as a professional.

It turns out my thought process couldn’t have been further from the truth. In actuality, it takes a great deal of maturity and self-awareness to admit to your own limitations. People respect that.

Moreover, you can only parade around pretending to be smarter than everyone else for so long. Eventually, that shit catches up with you. Before it does, though, you’ll likely have no trouble dishing out plenty of unproductive — and potentially harmful — advice.

Which leads me to my motivation for this post. Lately, I’ve noticed a number of fitness professionals on the wrong end of the law in this regard. While this problem certainly isn’t a new one, it’s come to a head lately, to the point where I feel compelled to speak out against it.

I figured a constructive way to tackle this would be to provide a few examples of what’s NOT okay to do when you’re in a position of authority. I solemnly swear never to commit the offenses described below, and — for the sake of the people we educate — I beg of my peers to make the same promise hereafter.

1. It’s not okay to prey on the lay public’s ignorance for personal gain.

Having a bunch of letters after your name lends an undeniable amount of instant credibility. And hey, you’ve probably earned it. What you haven’t earned, though, is the abuse of your credentials to manipulate the unsuspecting general public.

One common tactic for taking advantage of people goes like this:

Step #1 — Exaggerate the shit out of a minor issue or nonissue (i.e. “fearmongering”), typically in the form of vilifying a popular exercise or training modality.

One common tactic for taking advantage of people goes like this:

Step #1 — Exaggerate the shit out of a minor issue or nonissue (i.e. “fearmongering”), typically in the form of vilifying a popular exercise or training modality.

Example: “Push-ups are the worst exercise in the history of all exercises. If you keep doing them the way everyone does them, I guarantee you’ll have neck pain!”

Let's imagine the reader does push-ups all the time, but she’s never had neck pain. Wait… has she? She did tweak her neck that one time. Come to think of it, she did push-ups yesterday. Not only that, but her neck is also feeling a bit tense at the moment. Sweet lord almighty, Dr. Liarandthief is right! What should she do?!

Obviously, this is a scare tactic designed to draw the reader in and connect with them on an emotional level. The worst part is that it can create what’s called a “nocebo,” or the experience of pain because of the expectation of pain. Even though the reader never actually had pain as a result of doing push-ups, all of a sudden she does now.

Step #2 — Claim that you (and only you) have the solution to the problem.

Example: “Do this activation drill for the longus capitis and longus colli prior to doing push-ups, and the nociceptors in your cervical spine will never fire again!”

The average person doesn’t know their anterior cruciate ligament from their sternocleidomastoid. Sprinkle in a bunch of fancy-sounding anatomical gobbledygook, and they’re sure to buy in.

Step #3 — Sell your method.

Example: “For the low, low price of $97 $47, you get complete and instant access to my entire corrective exercise video library!”1

Voilà. Now that the reader is certain you’re a Hogwarts wizard, they’ll happily fork over some cash (at that bargain-basement price!) to stay pain-free from the pain they never even had to begin with.

2. It’s not okay to pretend to be an expert in something you’re not.2

Face it: you can’t be an expert in everything. In fact, deeper immersion in one specialty almost inevitably comes at the cost of more general knowledge. And that’s okay — as long as it’s acknowledged.

For example, suppose your background is in bodybuilding and powerlifting, and you work almost exclusively with that population. In all likelihood, you’re not qualified to give training tips to every footballer, field hockey player, rock climber, marathoner, yogi, and competitive square dancer who walks in the door. (Yes, apparently competitive square dancing is a thing.)

Expertise in one domain of fitness doesn’t automatically imply expertise in all of them. Instead of pretending to be the expert in those other areas, admit your limitations and refer out to professionals who are true experts.

Sure, you stand to lose out on a potential paying client. But you also stand to gain in terms of referrals sent back your way. Not to mention the good karma you’ll receive just for being a decent human being.

For example, suppose your background is in bodybuilding and powerlifting, and you work almost exclusively with that population. In all likelihood, you’re not qualified to give training tips to every footballer, field hockey player, rock climber, marathoner, yogi, and competitive square dancer who walks in the door. (Yes, apparently competitive square dancing is a thing.)

Expertise in one domain of fitness doesn’t automatically imply expertise in all of them. Instead of pretending to be the expert in those other areas, admit your limitations and refer out to professionals who are true experts.

Sure, you stand to lose out on a potential paying client. But you also stand to gain in terms of referrals sent back your way. Not to mention the good karma you’ll receive just for being a decent human being.

3. It’s not okay to state opinions as facts.

Again, the unsuspecting general public will believe just about anything. They’re definitely not going to PubMed fact-check you.

Consider the following two statements:

- “Studies show the barbell bench press is the most damaging exercise on the face of the earth. It should be avoided at all costs.”

- “In my experience working with general population clients, I don’t think the barbell bench press is worth the risk for most everyday people.”

The first is a hyperbolic blanket statement disguised as a research-backed fact. It’s meant to shock the reader. However, it’s missing some key information. Which specific studies support that claim? Also, what types of clients does this person train? Whether they realize it or not, the population they work with has a significant effect on their perception of the exercise.

The second statement is a clear and measured expression of a personal belief. It’s specifically based on experience working with a particular client population, which helps the reader decide if the statement applies to them. It’s not nearly as sexy as (A), which probably means it’s not going to get all the likes and shares, but it is honest.

The best approach of all would be to combine the science and the practice:

- “A 2007 study in the Strength and Conditioning Journal reported that subtle technical glitches in bench press performance can increase injury risk to the shoulder, collarbone, and chest. These findings jibe with my experience working with general population clients. For these reasons, I don’t think the barbell bench press is worth the risk for most everyday people.”3

4. It’s not okay to support individuals who repeatedly commit the above three offenses.

I’ll be the first to admit that I don’t know everything. I still have a lot to learn, both as a trainer and a scientist. But I do know this: as fitness professionals, people rely on us to help them get fit and strong while staying injury-free. They also trust us not to lead them astray.

I believe it was Uncle Ben from Spiderman who said “with great power comes great responsibility.” Even if he was only a comic book character, his counsel couldn’t have been more spot on.

If you’re guilty of any of the above items, please stop. If you realize you’ve been supporting someone who’s guilty of the above items, please stop supporting them. Otherwise, you too are part of the problem.

1 I understand that people have to make a living, and I have no problem with the $97 slashed down to $47 pricing scheme; it’s obviously a proven sales strategy. What I do have a problem with is Step #1 and Step #2 preceding Step #3. 2 My friend Todd Hargrove recently wrote a terrific blog post on how to differentiate between true experts and “gurus.” 3 For the record, I do use the barbell bench press with many of my clients. The statements above were just meant to illustrate my point.